We marvel at Stonehenge, Newgrange, and other megalithic structures and wonder how those ancient peoples—smaller and less enlightened than we—ever managed to construct such massive and meticulously arranged monuments. We struggle to comprehend a world in which time and patience allowed for sitting night after night, month after month, year after year to learn the shifting patterns of the black sky and the placement of the sun and moon—the celestial clockwork that birthed agriculture and paved the way for civilization.

But what our books, television programs, and tours seldom remind us is that those time-telling slivers of sunlight that the ancients so backbreakingly created through the alignment of tons of stone were devised to wake them from precious sleep. Their design often was intended to mark the life-sustaining solstices and equinoxes—which means someone had to be disagreeably awakened at dawn by that light to observe if the sun was rising precisely in that all-important position.

Someone’s sleep had to be sacrificed to mark the heavenly calendar.

Imagine spending twelve or fourteen hours pulling a 30-ton megalith, only to be told by the chieftain you have to get up at the crack of dawn to watch the sun rise while the rest of the tribe sleeps in. Our modern psyche can hardly comprehend such barbarity.

I can almost hear the disgusted, utterly indecipherable gripes in their long-dead language as the unfortunate groggily curses the life-giving sunlight that woke him but won’t give just fifteen more minutes.

Thousands of years later, on a continent undreamed of by those ancient peoples, I am wrestling with this age-old phenomenon: the hinge of the fifth Venetian blind of my bedroom window is irreparably broken.

Incapable of hanging in alignment with the rest of the blinds, it stands propped on the windowsill, leaning against the top of the façade. Although I have set the wayward blind at the best compensatory position to counter its gross misalignment, it still leans at—by my painstaking geometric calculations—a 3° angle. This may not sound like much, but—I assure you—this seemingly inconsequential gap transforms into a gaping chasm of painful sunlight come dawn.

My bedroom window faces south, which, in spring and summer, is not so much a problem thanks to the sun’s elevated path (although it would be even less of a problem if sunrise ceased coming so damn early in those months). But during autumn and winter, my bedroom window sits smack in the sun’s firing line as it traces its low course along the dipping ecliptic, the broken blind turning the sun into a blazing, creeping alarm clock that pours across my closed eyelids and mercilessly yanks me from slumber.

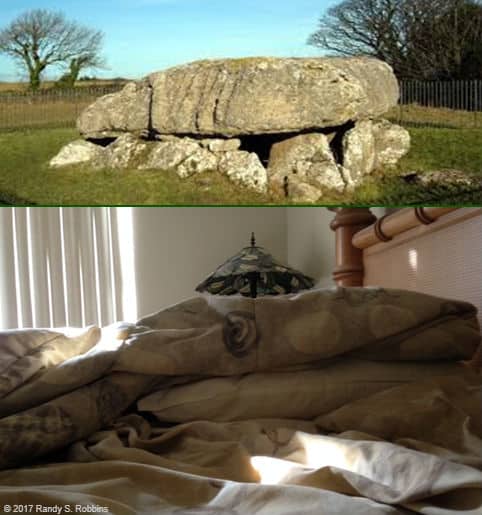

The language of the rudely awakened’s expletives has changed over the millennia, but the effect remains the same: my darkened bedroom alights like a hidden Celtic burial chamber on the first morning of winter, my bed an altar as sleep once again is sacrificed. I lie there, blaspheming the very entity that, with its rising, will allow me to lower my thermostat and reduce my heating bill, too jaded beneath the toasty comfort of my blanket to give thanks that it has risen at all and not left the world in blackened chaos.

Ironically, I suppose, my first reaction is to pull the spare pillow close, at a right angle to my own, and bunch the blanket upon it, creating a structure not entirely dissimilar to a capstoned burial cairn. Although the room now is suffused in light, my polyester-and-cotton cairn—quarried at Bed Bath & Beyond and hauled (albeit by car) across 2.7 miles of what is today known as Mount Laurel, New Jersey—manages to block the direct rays. If I am lucky, Caer Ibormeith, Celtic goddess of sleep, will permit me to again doze off (after which, if I am truly fortunate, I will not awaken as a swan). But life in a modern-day, ancient astronomical structure seldom forgives, and my rest usually is at an end the instant direct sunlight wedges between the blinds.

More than once while lying helpless in intrusive morning glare I have considered channeling the innovative spirit of Richard Dreyfuss’s Roy Neary by marching into the morning air, uprooting the hedges outside my bedroom, and tossing them through the open window to build an earthen Devil’s Tower in whose shadow I can return to sleep.

Frankly, about the only thing keeping me from actually doing it is that I don’t own a bathrobe…

Oh, the particularly cynical might say “Just get your non-Neolithic ass over to Home Depot and fix the damn hinge already.” And maybe they’re right. Why not avail myself of the technology of AD rather than wallow in the stagnancy of BC? After all, when was the last time I wore a loincloth or created fire with flint or died of old age before I turned 30?

Yet as I lie here, once again awoken 45 minutes before my alarm is set to activate, I sense a strange kinship with our remote ancestors. Between my sunlit bedchamber, the spine-tingling cries in the night of whatever small animal populates the nearby woods, and the need to seek out food daily due to my recently broken refrigerator, I’ve regressed a few steps toward that tantalizingly mystical time when the world was young, history had yet to be invented, humans lived symbiotically with nature, and the sky seemed alive.

And so, I must admit, for all the truncated sleep that I so dearly need, I’m drawn to this atavistic slice of life and its tenuous respite from our hyper-technologized, ready-made, too-easy world. It feeds my lifelong fascination for history and gives me a taste of life in a bygone era, whisking me from the soul-crushing mundanity of bill paying, and the life-sucking anonymity of being lost in a sea of millions, to a point where, through a few moments of pathetic escapism, perhaps I could be the one, however marginally, serving a pivotal role in society like that ancient solstice-spotter—all while still allowing the pleasures of indoor plumbing and the ability to slip on Levis and hunter-gather to the Dunkin’ Donuts at the far end of my parking lot to obtain pre-cooked, mass-produced sustenance.

So, to the more than 30,000 people who go unselected for the annual Newgrange Winter Solstice Lottery to experience dawn in one of the very burial chambers that once upon a time served this very purpose, I invite you to my place this December 21 for a celestial showing just as spectacular. It’s not like you’ll be waking me…