Every time I heard the phrase “don’t take it for granted” as a child, I genuinely could not grasp the concept because I thought people were saying “don’t take it for granite” and I only had a vague concept of what granite was. Then, I would quickly get back to eating raw brown sugar or throwing a stick at the side of my house.

But now, as I frantically ride this shantytown bicycle I call my life, I start analyzing how much “taking it for granted” is embedded into my being. I don’t mean hamfisted, obvious examples: I’m talking about things like bread.

Bread. What I eat when I haven’t gone to the grocery store and don’t want to. Bread with whatever will go on the bread. Or just dry bread. A bread sandwich. People have been eating bread for over 10,000 years. Quite literally hundreds of generations of humans have been sustained on some sort of bread, the same food that I shovel into my mouth with reckless abandon at Olive Garden. Bread is ubiquitous with just being a person or being in history class. It permeates time and space and Olive Gardens. People even believe ducks are supposed to eat it. They’re not.

But do you ever think of how many steps it takes just to make bread? And to invent bread, somebody somewhere had to invent flour. Do you know how many steps it takes just to make flour?

First, somebody is born. They live maybe 17 mediocre years. Then they wander outside the campfire, eat a delicious looking plant, and die a horrible death immediately. People freak. They don’t know what caused this death. In the span of time that the search party left the settlement and found the body, several other members of their village have also died from entirely unrelated causes. Such is the price of learning.

At the collective funeral, somebody goes out to gather edible-looking items and unknowingly brings the same plant in. Some people eat it and die immediately, adding to the funeral itinerary. Others saw them die from eating the plant. 2+2=poison plant and the association is made.

This happens for another few thousand years to countless scattered groups across the globe. People get better at knowing what kills them. Sort of. Through the process of fatal poisoning/diarrhea elimination, they accumulate a list of edible plants, including grains.

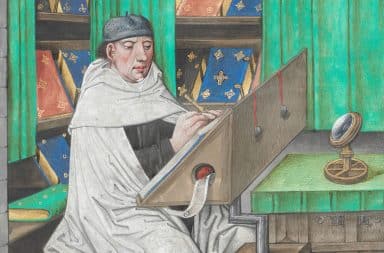

Somewhere along the way, somebody decides to take a big rock and start smashing these grains. I can imagine this was first met with the same reaction that me kicking your bowl of Chef Boyardee and insisting it’s a “good idea” would incite. Somehow this individual or individuals, whether on accident or via experimentation, found that sometimes food was better when it was thoroughly destroyed. The convincing might have gone something like: “Give me the food you just gathered after walking on sticks and rocks barefoot for four hours, I need to absolutely destroy it.”

Through some labyrinthian miracle of astounding proportions, not only did people figure that out, they eventually decided: “Okay, let’s turn this great, new, and delicious powder into a mushy paste and then try and burn it.” How many boring shifts at the temple of a sun goddess or orgies drunk on fermented milk had to happen for this conclusion to be made?

What do you think their first reaction was? “Oh shit! That’s weird.” Maybe they thought the powdered grain was poisoned now. Maybe they threw out hundreds of pieces of the first bread before they realized they could eat it.

Sometimes I get painfully high and watch How It’s Made. Everybody seems to be fascinated by the number of oddly shaped pieces it takes to make a toy shark, but I solely focus on the machinery making the toy shark. Who makes that? I feel my brain begin to narrow as I stare at a gear inside of a rubber belt at the end of a giant mechanical arm whose only purpose is to put the squeaker into the toy shark. Who made that arm? A bunch of people fumbling over toy shark production for decades until one accidental member revolutionized the squeaker placement? Also, why do toy sharks have squeakers?

But the toy shark community and lobby have the luxury of riding on the blood, sweat, and tears of millions of humans fumbling over how to control fire for several millennia to get them to this point. Rosters of nameless, forgotten, vitally important people figuring out that fire is hot to touch or bears are dangerous to pet.

Anybody who eats bread can thank these silent heroes as well. And as I reach into the crumpled plastic sleeve for the heel of my WonderBread loaf, I think about their sacrifices echoing into the abandoned halls of history.

I take a bite, remember that I don’t really like crust, and throw it away.