Vincent looked up from his desk to where Myra was still talking about her ex-husband and the beatings he used to give her. He resettled his glasses on his nose in a gesture that always gave off the impression that he was closely listening to whatever it was his patients were blathering on about and drifted off once again into daydream.

Drifted was perhaps the wrong word. He pursued the opportunity to daydream aggressively but lightly, the same way a little boy might chase a butterfly that he wanted to catch, but was at particular pains not to harm. This daydream was about his father. They were all about his father.

His father was a hardnosed man. He was also hard-bodied, hardheaded, hardworking and a touch hard of hearing. The last one was the most dangerous. The old man was particularly touchy at any implication that he was a less than perfect physical specimen and refused to acknowledge any mistake in hearing, instead supplying whatever his subconscious thought his hapless interlocutor might have said. Often, his subconscious supplied vicious insults in place of innocuous chatter, which gave him a chance to indulge his most favorite hobby.

Above all, he was a man who enjoyed beating his children. He subscribed to the belief that one should “spare the rod, and enjoy the hell out of it.” He had a few special tools for the task: A long, curved, beautifully crafted oak cane he had taken from a blind man who asked him for change, a length of piano wire that he had wrapped in duct tape until it was the thickness of his thumb, and his personal favorite, a pair of brass knuckles that he only consented to use on his children when he was very unhappy.

Or when he was exceptionally happy.

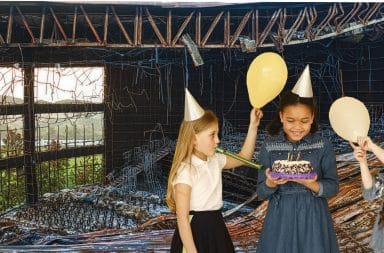

That was what made him different. Other parents beat their kids when they brought home bad report cards, or were noisy, or just too numerous; Vincent’s father beat his children completely on a whim. Vincent was quite as likely to receive a beating for bringing home a report card full of A’s as for getting arrested for arson. It had made him a slightly jumpy little boy, a habit he had only very recently grown out of.

Vincent begrudgingly made eye contact with Myra, where her eyes were red and puffy as she recounted yet another tale of spousal abuse. They all ran into each other in a way that made Vincent’s job both inane and laughably easy. She seemed reassured by this meaningless gesture and continued talking uninterrupted.

When Vincent was 9, his father had beaten him so hard and with such vigor that he had sprained his wrist. At first this seemed like a rare bit of good luck—for a week his father had been forced to use his off-hand, which took a lot of sting out of the blows. But his father was a quick study, especially when it came to his hobby, and soon was using both hands nearly equally well. Once in a while, he would even show off and beat two of his children at once, raining blows down in a cacophonous pain that as close as anything approximated a soundtrack to his young life.

An alarm sounded. The session was up. He got up to shake Myra’s hand and escort her out the door, careful not to touch her in a way that might be construed as unprofessionally affectionate. He settled back into his chair.

For the life of him, he couldn’t figure out why his ex-wife would use him as a therapist.