There I was. A burgeoning art collector accumulating some of the finest works of the 20th century into a masterful collection. I wasn't a classic insider in the art world; ingenuity was my momentum. More importantly than that, reputation was my spark plug.

I sent an advertisement to the New York Times. No bother with hiring a writer or publicist. I knew the business, how to make words crackle and turn heads. My picture would be on the front page of Sky Magazine. The good times rolled. I had it made…

It wasn't until the next month when I realized that my spellchecker had elided a costly malapropism. The headline of my advertisement, in blazing black and white, read:

"John Finklestein, Celebrated Fart Collector"

Of course, after investigating the ergonomics of my keyboard, I realized that the "F" key had been placed far too closely to the "A"—a costly error in a very literal sense. Immediately, I was the laughing stock of the art world. Exorcised from its center to the shame-stained walls of the margin.

John of the Cross speaks of a Dark Night of the Soul. And this truly was such. I couldn't go to a party or a show at an independent coffee shop without someone making a snide remark. "This is John Fecalstein everyone…oh, I'm sorry, FINKLEstein, he's a fart collector, anybody know that?" "Oh, Mr. Finklestein, your exhibit sounds flatulous!"

All your New York City friends go to exhibits for these weirdos who jizz on a canvas and call it art. Look. That jizz ain't art. I could only respond with slow, punctuated ejaculations of laughter: "Ha. Ha. Ha." (Already, at that point, I was forced to absolve myself of my favorite word "ejaculation" as people somehow connected a perfectly respectable word used to describe sudden expressions of elation or surprise to the expelling of noxious, methane gas from one's rectal aperture.)

I could have given up at that point. A marble bust of my father, Frederick Finklestein, sat on my desk. He was a celebrated chemist, but he dreamed of developing his own business. When he had saved enough money up, he was able to do so. His entrepreneurial career was not sparkling, but he was innovative. He'd patented a scent that he called "New Horse Smell" that could be sold to equestrians. A few of them caught on to the trend. Unfortunately, most of the professional horse racing public were too backwards to understand the powerful new product on the market. My father was so innovative that he failed.

I often spoke to him, seeking business wisdom. Sitting at my desk, after ruthless humiliation, I looked up to his stone eyes, feeling wholly unworthy. "Where do I go from here?" I asked.

To my surprise, he spoke: "Worthless boy-child, why do you continue to bother me?"

"I am publically humiliated, horrified at my own imperfection…. Father, should I give up?"

He was silent for a long time, then he cleared his throat.

"Yes…give up…"

I nearly did, but I discovered a group of fiendish ne're do wells crouched under the window of my house, impersonating my father almost dead-on. So, instead, I sat down and asked myself how I could turn this media fiasco on its head. That was when I consulted my cousin in Alabama, a Mr. Roy "Hoss" Johnson. He was a successful entrepreneur, having opened up a chain of car washes throughout the state. I had, only recently, lost my tenure as assistant art professor at New York University. I was considered "vulgar." My apartment in the Upper East Side was revoked by the local community board as a result of a clause in their contract that disallowed references to bodily functions.

It was at Roy's home, after a dinner of grilled cheese sandwiches by candlelight (a Friday night ritual that we had carried on for several months), that Roy told me to follow him downstairs. He took me to his basement and then to a side room hidden behind a poster of Lynyrd Skynyrd. It was there that he showed me walls of jars, each labeled with a specific day, month and year.

"What is this?" I asked Roy.

"John," he said, "this is my fart collection."

"I do not appreciate your mockery."

"No," he said, "every jar is labeled. I've done this since I was a boy. I have collected my farts. And when I read that you were doing the same thing, well, I felt overjoyed. Finally, someone else to talk to about this."

Now, it took me a few seconds to realize that Roy, as a result of his simple-minded Alabama upbringing, had no idea that my New York Times headline was an error. He actually thought I collected my own flatulence.

"No, Roy, this is not what you think."

"John, I think you need to listen. Because what I have here can make you a fortune. Think about it. All your New York City friends go to exhibits for these weirdos who jizz on a canvas and call it art. Look. That jizz ain't art. It's hardened and nobody believes that it could still impregnate a woman. This here? If you open one of these jars, it will still have the devastating impact that it had two, five, ten or even twenty years ago."

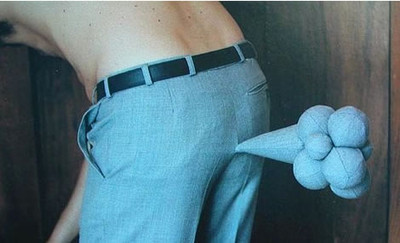

I proudly held the open jar to his exposed buttocks as he flatulated for two whole minutes."You have a 20-year-old fart in here?"

"John, cut the crap. We're going to do this."

So began the homegrown movement of fart collection. It was a difficult beginning. Yes, we were able to sell Roy's farts to locals. It was truly vaudevillian. Roy simply pasted a sticker of Dale Earnhardt or Larry the Cable Guy onto a jar and claimed that he had surreptitiously obtained that bodily gas from the celebrity personality by impersonating a proctologist or some other wild, nonsensical claim. Much to my surprise (and chagrin), he succeeded.

But I cautioned him that we would never succeed in convincing people in civilized society, such as the Upper East Side, to invest in such filth.

Yet, he did his research. He looked up the names of famous people, printed out the pictures and plastered them on the side of his Mason jars, over the yellowed tags reading "2/13/78" or "18th Birthday" or "First Date." Suddenly, they became the rare and much sought after bodily expulsions of Robert Mapplethorpe or Andy Warhol.

Within a year, Roy and I were at the top of the art world. The MOMA was asking for a collection of jars for a two-week exhibit. Roy even orchestrated a jar that allowed viewers to "smell test" different celebrities and authors' scents. You may remember this exhibit. It ran for a record thirteen months at the Guggenheim.

Of course, Roy had always been careful to only display the "farts" of dead personalities. Otherwise, our entire scheme would have been uncovered.

It wasn't long before we were being sought out by celebrities who wanted their gases collected. They brought their own jars. Roberto Benigni was the first, having heard of our controversial series of Benito Mussolini's collected farts at The Morgan Library. He presented a beautiful jar of glass infused with sapphire as he had heard that this maintained the full integrity of one's methane gas.

I proudly held the open jar to his exposed buttocks as he flatulated for two whole minutes. When Roy had deftly covered the jar, Roberto turned around with a deep smile. "I have saved that for an entire week. I will remember this forever."

He allowed us to display this jar in the Menil collection. Most people there had no idea who Roberto Benigni was, but it didn't matter. The beauty of the jar and the magnificence of the humanity contained therein tugged at their hearts. People actually wept.

Five years after my public shaming, I was back again. On the cover of the New York Times. This time, I didn't pay. It was an article: "Fart Collector Raises a Stink". The clever wordplay was only part of a masterfully written article that truly captured the soul of what had become a deeply personal affair. We were capturing humanity, a slice of it, a moment of it.

Now, when I went to parties or independent coffee shops, they spoke of me by the title "Fart Collector" with a sense of awe. I lithely walked the street of Paris, Hong Kong, San Francisco. I was back. Back in a big way.

As for Roy? I owe him everything. He helped me raise myself from the ashes, to soar like a phoenix above the smoldering ruins of my former career—a career that I realize now was a waste of time, a road leading to the collection of jars containing farts falsely attributed to dead celebrities, artists, and political leaders.

As far as profits? Roy and I are the wealthiest art collectors in the modern world. Our works have travelled all over the world. I have even heard that there is a jar of Marlon Brando's farts that is worshipped by the Ndebele in Africa.

Failure doesn't mean you give up. That's what I've learned. It means you begin looking somewhere else. Somewhere deep inside you. For Roy, it was a 25-year collection of his bodily gas that would otherwise have languished in the basement of his Montgomery, Alabama home. For me, it was realizing the old post-modern maxim that low art and high art don't exist. Only art.

Just this morning I was re-reading an interview I had in Sky Magazine. They asked me, "So, Mr. Finklestein, have you ever collected your own farts?" And I replied, "I have been doing it my whole life." And they did not know what I meant. And I did not know either.

But it hardly mattered. Because I was rich and no longer needed to make sense anymore.